50 years ago today: The wedding that almost wasn’t

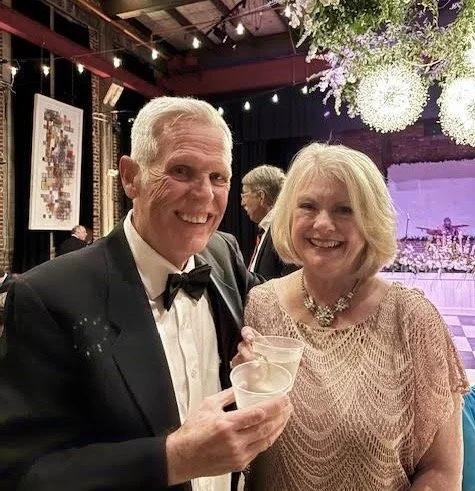

My wife and I got married fifty years ago today.

The wedding almost had to be called off.

We were two years out of college, living in St. Louis. Our wedding was scheduled for Saturday, December 27, in her hometown of Hannibal, Mo., where her parents were pillars of the community. Her father, Dennis, was a lawyer and judge. Her mother, Dorothy, was a teacher and church music director. Judy was well-known, too. At 18, she had been crowned Miss Hannibal, but lost the Miss Missouri pageant to a cross-eyed girl who tap-danced to “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.” (She remains bitter about it to this day.)

That summer, when we told Judy’s parents we were engaged, Dorothy—a no-nonsense, hyper-efficient woman who had served as a WAVE in World War II—decreed that the wedding would take place the Saturday between Christmas and New Year’s. That was convenient for her because it fell squarely in the middle of her school’s holiday break.

Formal, reserved, prim, and so proper she made Emily Post look like Amy Winehouse, Dottie intended to obsess over every detail to ensure her only daughter’s wedding came off like the Royal Wedding (for Hannibal) it should be.

My future father-in-law, Dennis, was easygoing and affable—I liked him the moment we met—but Dorothy scared me shitless. She had already expressed her displeasure that I didn’t have a master’s degree, which I took to mean she doubted I would ever be able to support her daughter in the style to which she had become accustomed.

Despite any misgivings she may have had about Judy’s choice of a life partner, over the next few months Dorothy reserved the church, arranged the premarital counseling required by the minister, chose the music, ordered the flowers, met with caterers, had the invitations printed and mailed—everything. The one thing she couldn’t do was get our marriage license. Because we lived out of town, Judy and I decided we would do that in St. Louis. The license was issued by the state, so it was valid in any county.

Missouri in 1975 required couples applying for marriage licenses to undergo blood tests to ensure neither had syphilis, a venereal disease whose initial symptoms include chancre sores, fever, headaches, and/or hair loss. In its early stage, syphilis can be cured with a single shot of penicillin. If left untreated, the disease enters a latent stage: symptoms disappear, but the infection remains. Ten to thirty years later, it can return as tertiary syphilis, causing insanity, blindness, deafness, heart disease, stroke, and death.

On Wednesday, December 17—ten days before the wedding—Judy and I went to the St. Louis County Health Department to have our blood drawn. We were told to return two days later to pick up the results so we could proceed to the Marriage License Bureau.

The Health Department was down the street from my office, so we agreed that on Friday I would pick up the results and meet Judy at the License Bureau during our lunch hours.

I told the clerk I was there to pick up the Dryden-Davidson test results. She handed me an envelope. I opened it in the parking lot.

There was an “X” in the box marked negative for syphilis on Judy’s test.

The “X” on mine was in the positive box.

My first thought was, How can this be? I vaguely remembered from high-school health class that early symptoms of syphilis could disappear on their own. The disease then went dormant. That must be what had happened. Perhaps I had overlooked a fever, headache or the loss of a few hairs from my head, but how in the hell could I have ignored a chancre sore—or sores—anywhere on my body, much less on my you-know-what?

My second thought was Judy. How was I going to explain why we couldn’t get our license?

My third thought was of something far more disturbing — Dorothy. How would she react when she learned that the wedding she had planned for months—the wedding relatives were flying in from Seattle and New Orleans to attend, the wedding to which she had invited 200 guests, the reserved church and minister, the Hannibal Country Club reception—had to be canceled because her under-educated future son-in-law had VD? And not some garden-variety VD like gonorrhea. Like Henry VIII, Ivan the Terrible, Hitler and dozens of other crazed historical figures and probably half the patients in the state insane asylum, he had syphilis. Even if he were someday cured, she’d never let him anywhere near her daughter.

When I met Judy at the License Bureau, I couldn’t speak. I handed her the envelope. She opened it and read the contents. Though horrified—what bride-to-be wouldn’t be?—she immediately said the test had to be wrong. I needed to go back to the Health Department and demand a retest, because I most assuredly did not have syphilis.

I weakly offered, “Maybe I got it in college—or during the summer I backpacked around Europe—and the symptoms were so mild I thought they were something else?”

She reiterated that I needed to go back immediately. (She has always been the calm partner in emergencies. Every marriage needs one.)

She returned to her office. I did not.

Instead, I went to the library, where I spent the afternoon poring over medical journals filled with black-and-white photos of chancres covering sufferers’ genitals, hands, arms, trunks, and faces. I learned everything there was to know about the primary, latent, and tertiary stages of the disease while racking my soon-to-be-driven-mad-by-syphilis brain to figure out how—and from whom—I had contracted it.

Then I went to a bookstore in search of medical books written for laypeople. The photos in those were even worse: close-up color images of oozing chancre sores that looked like greasy pepperonis.

By the end of the day, I was convinced that, despite having no symptoms, I had been infected for years. I considered returning to the Health Department to demand a retest on the off chance I was wrong, but couldn’t bring myself to do it. Would the clerk laugh at me? Would people in line overhear our conversation? Would the nurse drawing my blood wear a hazmat suit?

The Health Department was closed for the weekend, leaving me two full days and three sleepless nights to contemplate those scenarios—and the look on Dorothy’s face when I fell to my knees sobbing like a syphilitic madman.

Judy and I discussed how we might break the news to her parents if the result of the re-test confirmed the positive diagnosis of the first. Would we be able to avoid doing that by meeting privately with the minister, explaining the situation, telling him I was undergoing treatment, reminding him that God forgives sinners, and begging him to perform the ceremony anyway, promising to provide a post-dated license he could sign once we had it in hand?

I was waiting in the hallway outside the Health Department when it opened Monday morning.

I told the clerk why I was there and handed over my positive test result. She took it into the back room and returned a few minutes later, looking stricken.

“I checked your file,” she said. “The X should be in the negative box, not the positive. It’s a misprint—the paper fed through the printer wrong. It’s happened before. I’m so sorry.”

She handed me a corrected report.

I couldn’t decide whether to kiss her or jump over the counter and strangle her.

That was Monday. Christmas was Thursday. The wedding— which came off exactly as Dorothy had planned it except for the sleet that began falling as we ran through a shower of rice toward my orange Pinto to leave for our honeymoon —was Saturday.

We never told anyone how close the wedding came to disaster—until two weeks ago after downing multiple glasses of Champagne at a family wedding, when we told our sons and their partners. After their initial horror, they started laughing, then laughed even harder imagining how their grandmother would have reacted to the news.

After fifty years of married life with Judy—who, despite my lack of a master’s degree, has stuck with me through sickness (including possible syphilis) and health, for better and worse—I can finally laugh about it too.

Postscript:

While the heroine of this story is obviously Judy, this post was written in memory of my mother-in-law, Dorothy, whom I came to admire and respect. I never told her I loved her—she wasn’t the kind of woman comfortable discussing such things—but I did.

I could never have been brave enough to tell this story to her face. But I like to think she is laughing—or, as she called it, chuckling—as she reads this up in heaven, where she is no doubt politely but firmly keeping the angels in line.